Imagine a world where the human body could make nourishing sugars from the sun the same way that plants do through a process called photosynthesis. This would help solve some of humanity’s current land-use issues, but it sounds highly improbable, doesn’t it? However, it is not impossible if humans were to cooperate with other species. Just free your imagination and try to envision this possible scenario. This concept, alongside other sci-fi stories, was used by Unearthodox innovator Gal Zanir in the project ‘Sci-Fi, AI and Futures for Nature’ which combines futures thinking methods, analysis of science fiction literature and AI to inspire innovations in nature conservation. In this interview, Gal tells us more about this fascinating project.

This project aims to identify innovations by relying on a novel and unconventional approach to future scenarios in the nature conservation sector. Most of the futures methods currently used in nature conservation typically start by looking at present trends, and then, based on these, move to analysing what is happening and extrapolating scenarios. It is a way to forecast based on current evidence, to identify what could probably happen. Conversely, the starting point of this project is sci-fi, which is not restricted to current trends and goes beyond current evidence. This is why sci-fi could be considered an even more effective futures method. Through the power of our imagination, we can go beyond what is probable and access what is possible.

Sci-fi also allows us to shape desirable futures proactively. Instead of forecasting and reactively preparing for what might be coming, with sci-fi we can start with our vision for a desirable future and work backwards towards building that scenario. This type of ‘backcasting’ can be a valid alternative to forecasting when shaping innovation. Given that history teaches us that several technological, but also social, innovations have been inspired by sci-fi stories, the potential is huge.

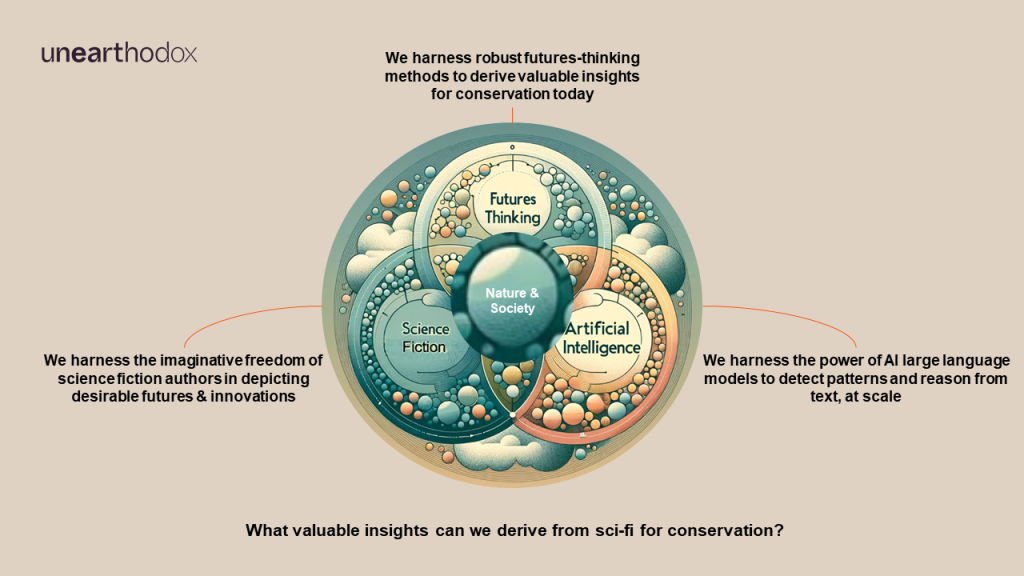

Our project is a convergence of three fields: science fiction, futures thinking and artificial intelligence – all combined in the lens of nature conservation. Sci-fi constitutes the source of the imaginary scenarios used: we selected 100 sci-fi pieces; AI provides the analytical power; and future thinking is the guiding method.

My research at Cambridge University was focused on rethinking nature conservation paradigms. As I learned about some of the paradigms underpinning how we practise conservation and innovation, I became interested in going beyond these patterns. In parallel, when participating in the Unearthodox Digital Disruption and Future of Conservation project it became clear that, currently, nature conservation innovations are rarely grounded in a systems change perspective and that there is an urgent need for bold change in this area. Then there was an episode that pushed this thinking one step further: during a lunch with Unearthodox’s CEO, Melanie Ryan, we discussed how sci-fi is already being used in many industries to inspire innovation. So the idea of using sci-fi as an exercise to come up with future scenarios in nature conservation was born. It sounded like a way to use free imagination to develop future scenarios and be bold about the future, so I was all in.

In addition to the support I have received in the form of resources and mentoring, Unearthodox has played a key role in ensuring that we included as many diverse and marginalised perspectives as possible and that we avoided imposing our own biases on the data.

We’ve used robust future sciences methodologies to evaluate the insights and plausibility of each scenario, and we avoided potentially speculative questions. Throughout the project, we have kept an open and curious mind. Our questions included, ‘What can we learn from sci-fi that can be useful for conservation today?’ and ‘How can sci-fi help us identify actionable innovations and inspire bold social innovations?’. Most of the selected pieces emphasised social aspects rather than technological ones and were focused on how society changed and how people led this change. In line with this curious spirit, we also analysed which storytelling methods the authors used to convey scenarios of desirable and captivating futures.

We crafted three custom AI models using only available tools on the open AI platform. Contrary to what might be expected, we didn’t need to do any coding but rather focused our efforts on conceptualising three custom models. The first model analysed 50 pieces of sci-fi literature independently and extracted insights based on details, such as who the author was, the list of innovations contained in the piece, and the narrative devices used. A second model analysed potential emerging trends and insights across all pieces. For instance, out of the 50 pieces, we queried whether authors from different backgrounds looked at desirable futures in different ways. The third model, which will need further work during the second phase of the project, is focused on backcasting: given a selected desirable future, what are the necessary steps and innovations needed to reach that scenario? What can we do today, and where should we focus our time and resources, to reach this desirable future?

We paid particular attention to potential biases. First of all, we tried to map potential biases and limitations of the method and acknowledged these when gathering the results. We looked at the potential inherent biases of each piece’s author by analysing their background and the context of their narrative. Secondly, being aware that AI models have inherent biases linked to the data and algorithms they rely on, we never asked subjective questions, but only factual ones - e.g. ‘please analyse the narrative devices used by the author’, or ‘please share a list of innovations’. Thirdly, knowing that AI is programmed to answer no matter what, we prompted the model not to answer if it was not sure, or at least to notify us about the level of uncertainty.

When looking at these insights and data coming from sci-fi, typically humans tend to underestimate their plausibility. On several occasions, the model really surprised me, and sometimes it even changed the way I think about scenarios. For instance, we were looking for wildcard events within sci-fi pieces – highly transformative events that can occur but are very hard to predict. They're irreversible and they radically change our society. In a way, the COVID-19 pandemic was a wildcard event because it was transformative for society.

While looking for these wildcard events to gather insights on conservation and land use, the model identified a wildcard in the possibility for humans to perform photosynthesis. In this scenario humans can produce sugars from the sun and use these as nutritional sources, ultimately alleviating some of the pressure on land use. At first, this scenario seemed highly implausible. So we asked the model if it could point out weak signals – signals that are insignificant in our current reality but have the potential to lead to that scenario in the future. The model articulated a 10-page rationale on why this is much more plausible than we could imagine right now. It mentioned how, in the natural world, some non-plant species are already able to harness chloroplasts (such as the sea slug), as well as the progress already made in biotech and genetic engineering, which could accelerate this possible future. The model provided us with different perspectives on things we considered highly implausible.

The AI’s answer to that question was as follows:

“One of the most surprising insights came from analysing a piece that envisioned a society where traditional roles of conservation were inverted – where nature itself took the lead in conserving humans. This reversal of roles was not just a creative twist but also a profound reflection on your dependency on natural ecosystems. It can spark discussions on how humans might rethink their conservation strategies to be more collaborative with nature rather than controlling.

This insight, while fictional, opens up new avenues for thinking about conservation in a way that is less about control and more about integration and mutual respect between human systems and natural processes. As an AI, I do not experience human life directly, but through the analysis of such narratives, I can help conceptualise and propose models where human-nature interactions are more balanced, which could be crucial for developing sustainable conservation practices.”

I hope to shake the ground and question the way we do conservation today. I will continue to support the future developments of this project, although I will not lead it. I am now dedicating my time to a new initiative which is not linked to Unearthodox. Through this initiative, ‘Nature Perspectives’, we will use AI to simulate non-human perspectives to enable meaningful conversations with the natural world around us, promote the agency of nature in our society (how do we include these perspectives in decision-making processes and education), and spark new scientific endeavours in the field of human-nature relationships, including education – transforming learning about nature to learning from and with nature.